On this page

- E1

- E1.1

How does Viet Nam’s policies, laws and regulations define natural forests and biodiversity?

- E2

- E2.1

- E2.2

What are the outcomes for non-conversion of natural forests in Viet Nam?

- E3

- E3.1

- E4

Incentivising the conservation of natural forests, biodiversity and ecosystem services

- E4.1

- E5

- E5.1

How does Viet Nam seek to enhance the social and environmental benefits of REDD+?

- E5.2

What are the social and environmental trends in Viet Nam’s forested areas?

Viet Nam’s natural forests are differentiated from planted forests based on the origin of the forest, with natural forests clearly defined as those “existing in nature or restored by natural regeneration”[1]. The natural forest can be categorised into different types and forms based on the extent of stable forest structure (primary forests and secondary forests). Primary forests are the forests which have not yet been or are less influenced by humans or natural disasters and have a relatively stable structure, while secondary forests are forests that are influenced by humans or natural disasters, leading to changes in their structure. Secondary forest includes naturally restored forests, which are forests formed through natural regeneration on land areas that were previously deforested due to agricultural expansion, forest fires or exhaustive exploitation, and post-exploitation forests, which are forests that have undergone the exploitation of timber or other forest products.

Viet Nam defines biological diversity as the abundance of genes, organisms and ecosystems in nature[2].

[1] MARD Circular No. 34/2009/TT-BNNPTNT (2009), Article 5; the Law on Forestry (2017), Article 2(6). Vietnamese; English

[2] The Law on Biological Diversity (2008), Article 3(5). Vietnamese; English

Viet Nam defines biological diversity as the abundance of genes, organisms and ecosystems in nature[1].

[1] The Law on Biological Diversity (2008), Article 3(5). Vietnamese; English

In Viet Nam, conversion of forests means a change in the purpose of primary use of the forest that results in a change in the forest classification of the forest. Conversion of natural forests, therefore, means a change in the purpose of primary use of the forest that results in a change in the classification of the forest from natural forest to a non-forest or plantation forest classification (e.g. to plantation or to agricultural land). The requirements and conditions for repurposing of forests and the powers to convert forest use are regulated by Vietnamese law[1].

Under the Law on Forest Protection and Development (2004), changing the use purpose of natural forests to another use purpose must be based on the conversion criteria and conditions prescribed by the Government[2]. The recently approved Law on Forestry (2017, effective 1 January 2019), explicitly prohibits the conversion of natural forests (except in cases of nationally important projects, national defence projects, or other critical projects approved by the government)[3]. The requirements for Environmental Impact Assessment and Social Impact Assessment in the development of master land use plans and assessment of potential REDD+ benefits and risks for Provincial REDD+ Action Plans (PRAPs) also prevent planning for the conversion of natural forests[4]. Implementation guidelines have not yet been issued for the new Forestry Law (2017); these will be prepared for consultation, revision and approval.

The Ministry of Agriculture and Rural Development (MARD) is the focal point for implementation of forestry laws in Viet Nam. The Ministry of Defence, the Ministry of Public Security, the Ministry of Natural Resources and Environment, and other ministries and ministerial-level organizations are responsible for collaborating with MARD in performing state management of forestry within the scope of their tasks and powers.

At the provincial level, the Departments of Agriculture and Rural Development are responsible for developing PRAPs for appraisal and approval by the Provincial People’s Committees. The Ministry of Natural Resources and the Environment, and provincial Departments of Natural Resources and the Environment within their respective localities, are responsible for oversight, appraisal and approval of social and environmental impact assessments.

[1] The Law on Forestry (2017), Articles 18-21. Vietnamese; English

[2] The Forest Protection and Development Law (2004), Article 27. Vietnamese; English; see also Government Decree No. 23/2006/ND-CP. Vietnamese; English and the Prime Minister’s Decision No. 34/2011/QĐ-TTg. Vietnamese; English

[3] The Forestry Law (2017, effective 1 January 2019), Article 14. Vietnamese; English

[4] Government Decree No. 18/2015/ND-CP; MARD Decisions No. 5414/2015/QD-BNN-TCLN. Vietnamese; English

A number of potential benefits and risks related to the non-conversion of natural forests, and their biodiversity and ecosystem services, have been identified through REDD+ planning processes at the national and subnational levels. These benefits and risks, and measures suggested to enhance benefits and reduce risks, are discussed in detail under Safeguard E3.1.2, which looks at the conservation of natural forests and biodiversity. Safeguard E3 also provides information on National REDD+ Programme policies and measures that support conservation of natural forests.

- Trends in natural forest cover

-

The following information shows the status and trends for a number of indicators related to natural forests in Viet Nam nationally. These figures provide an insight into the progress of implementation of relevant regulations to prevent the conversion and promote the conservation of natural forests, and of national-scale implementation of relevant REDD+ policies and measures.

Natural forest cover statistics

Table showing natural forest cover (in three management categories) versus plantation and other land in percentages or ha, nationally and by forested province

Table showing natural forest cover (in three management categories) versus plantation and other land in percentages or ha, nationally and by forested province

Area and forest cover rate of Vietnam 2021

Year 2021 [1]

Area with forest (ha)

Natural forest (ha)

Plantation forest (ha)

Forest cover rate (%)

Total of the country

Total

14.745.201

10.171.757

4.573.444

42,02

Northwest

Total

1.808.285

1.584.974

223.310

47,06

Northeast

Total

3.970.714

2.331.602

1.639.112

56,34

Red river delta

Total

83.326

46.326

37.000

6,18

North Central

Total

3.131.061

2.201.435

929.625

57,35

The coastal

Total

2.451.496

1.566.677

884.820

50,43

Highlands

Total

2.572.701

2.104.097

468.604

45,94

South East

Total

479.871

257.304

222.566

19,42

Southwest

Total

247.748

79.341

168.407

5,44

[1]Attached to Decision No: 2860/QĐ-BNN-TCLN July 27, 2022 of the Ministry of Agriculture and Rural Development

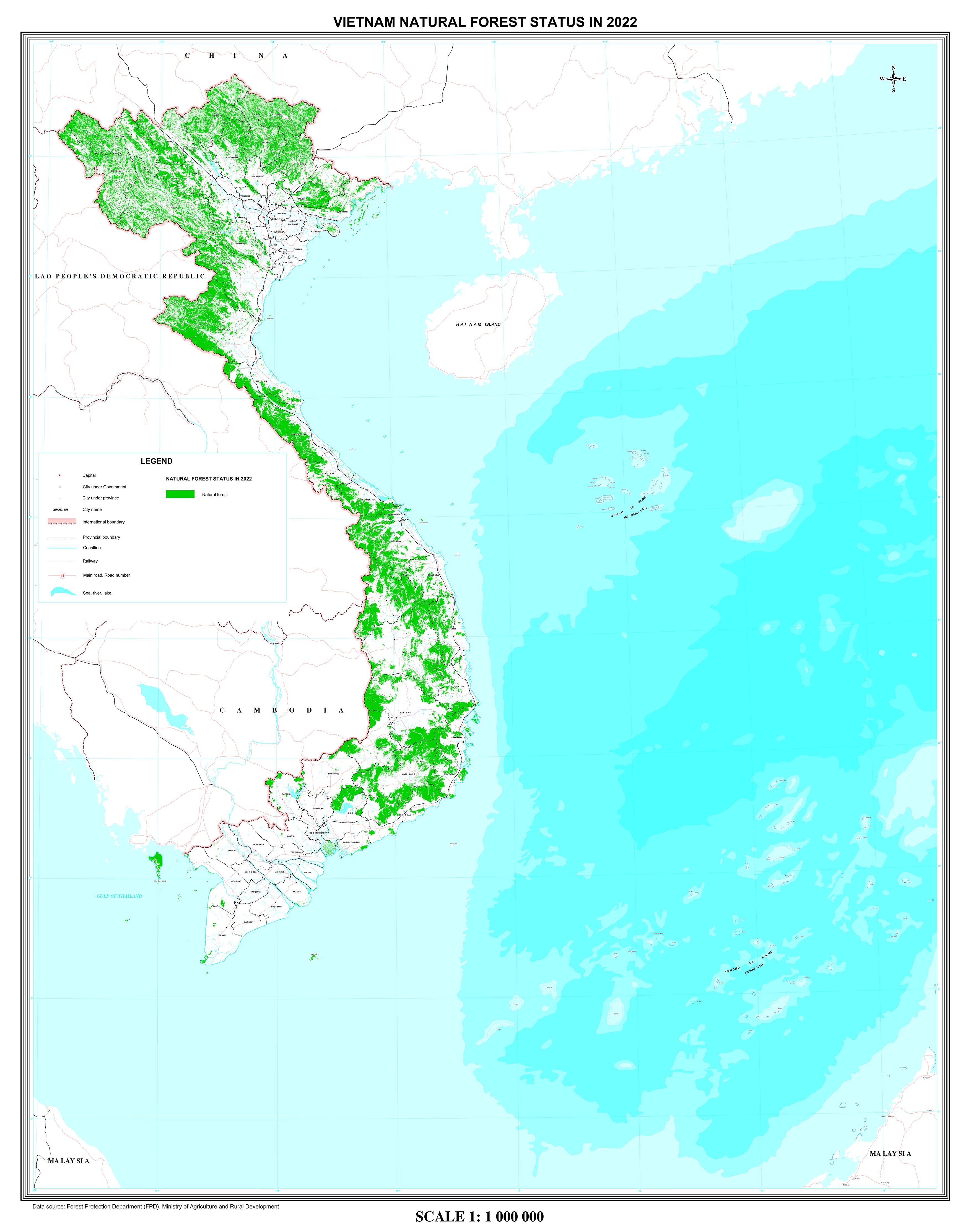

Natural forest cover map in 2022 -

Map of current status of natural forest vs plantation and other land

Map of current status of natural forest vs plantation and other landConversion of natural forest nationally

Table showing change in natural forest nationally and that has been converted to other forest/land use classes[1]

Table showing change in natural forest nationally and that has been converted to other forest/land use classes[1]

-

- Trends in other land and ecosystem types

- Content not yet available.

Viet Nam defines conservation of natural forests as protection of forests. Activities that directly affect forest ecosystems, as well as the growth and development of forest organisms, must comply with the provisions of law[1]. From 1 January 2019, conversion of natural forests will be strictly prohibited, except in cases of nationally important projects, national defence projects, or other critical projects approved by the government[2].

In Viet Nam, conservation of biodiversity means: the protection of the abundance of natural ecosystems which are important, specific or representative; the protection of permanent or seasonal habitats of wild species, environmental landscapes and the unique beauty of nature; the rearing, planting and care of species on the list of endangered precious and rare species prioritised for protection; and the long-term preservation and storage of genetic specimens[3].

Viet Nam also has a number of policies, laws and regulations that support the conservation of biodiversity. Stakeholder participation in forestry development, environmental protection, biodiversity conservation and the provision of environmental services is required, in order to help eradicate hunger, eliminate poverty and enhance living standards in rural mountainous areas[4]. Key ecosystems and biodiversity areas, threats to biodiversity, and priority in-situ and ex-situ conservation measures have been identified, and specific tasks assigned for the conservation of particular zones in the country, including the development of conservation corridors[5].

Forestry planning is required to be consistent with national strategy on biodiversity[6]. Conservation of natural ecosystems which are important, specific or representative for an ecological region and the conservation of threatened species is prioritised[7]. The illegal extraction of natural resources is prohibited, and socio-economic assessments are required to be carried out on socio-economic development strategies as well as strategies and plans for the utilisation of natural resources[8].

Environmental impact assessments are to be carried out in land parcels situated in wildlife sanctuaries, national parks, historical - cultural monuments, world heritage sites, biosphere reserves, scenic beauty areas - that have been ranked or projects that can cause negative environmental impacts[9]. Environmental and social benefit and risk assessment is also required during the development of Provincial REDD+ Action Plans, including consideration of the impact of policies and measures on biodiversity[10].

The Ministry of Natural Resources and the Environment, and provincial Departments of Natural Resources and the Environment within their respective localities, are responsible for special projects on biodiversity conservation throughout the country. Provincial Departments of Agriculture and Rural Development and Forest Management Boards (especially those for Special Use Forests), are responsible for the conservation of forests and wildlife within their respective localities and sites.

[1] The Law on Forest Protection and Development (2004), Articles 41-44. Vietnamese; English; See also: The Forest Development Strategy for the period 2006 to 2020; the Law on Environmental Protection (2014). Vietnamese; English

[2] The Law on Forestry (2017, effective 1 January 2019), Articles 18-21. Vietnamese; English

[3] The Law on Biodiversity (2008), Articles 3(1), 8, 11, and 25. Vietnamese; English; See also: The Forest Development Strategy for the period 2006 to 2020 (2006); the Biodiversity Law (2008). Vietnamese; English and the National Biodiversity Strategy to 2020 with a vision to 2030 (2013) and the accompanying National Master Plan on Biodiversity Conservation adopted according to Prime Minister’s Decision No. 45/2013/QD-TTg. Vietnamese; English; the Law on Environmental Protection (2014). Vietnamese; English; the Forestry Law (2017), Article 10. Vietnamese; English

[4] The Forest Development Strategy, 2006-2020.

[5] Prime Minister’s Decision No.1250/2013/QD-TTg; Prime Minister’s Decision No. 45/2014/QD-TTg.

[6] The Forestry Law (2017), Article 10. Vietnamese; English

[7] The Law on Biological Diversity (2008), Article 5. Vietnamese; English

[8] The Law on Environmental Protection (2014), Article 13. Vietnamese; English; Decree No. 18/2015/ND-CP.

[9] The Law on Environmental Protection (2014), Article 18. Vietnamese; English; MONRE Circular No. 27/2014/TT- BTNMT. Vietnamese; English; MARD Circular No. 09/2014/TT-BNNPTNT. Vietnamese; English

[10] MARD Decision No. 5414/2015/QD-BNN-TCLN.

The principles, goal and specific objectives of Viet Nam’s National REDD+ Programme (2017)[1] refer to the conservation and enhancement of natural forests. For example, one of is 2017-2020 objectives is to ‘improve the quality of natural forests and planted forests to increase carbon stock and environmental forest services, replicate effective models of forest plantation, sustainable management, protection and conservation of natural forests’.

A number of policies and measures in the National REDD+ Programme are aimed at the conservation of natural forests, and can be expected to support the conservation of these forests’ biodiversity and ecosystem services. For example:

- Continue to review and adjust the land use master plan and provincial land use plans to reach the target of 16.24 million hectares by 2020, including the promotion of environmental impact assessment;

- Promote sustainable and deforestation-free agriculture and aquaculture, such as piloting and replicating sustainable and climate resilient models for aquaculture, coffee, rubber and cassava;

- Pilot, evaluate and replicate sustainable models for natural forests enhancement, protection and conservation, including in natural production forests and special use forests, and forest rehabilitation and enrichment with native species; and

- Enhance the economic and financial environment for forests, including the economic valuation of forests and integration of forest values into national financial processes (e.g. GDP).

In addition, environmental and social co-benefits and risks of the National REDD+ Programme policies and measures were assessed in 2017, and co-benefit enhancement and risk mitigation measures suggested. This includes a number of benefits and risks related to the conservation of natural forests and biodiversity:

- Conservation of biodiversity may be improved through maintaining natural forests or restoring forest ecosystems, and through maintained or improved connectivity of forest habitats;

- There may be improved or maintained supply of forest goods and ecosystem services (natural capital);

- Resilience and adaptation to climate change and its associated effects may be increased;

- Ongoing loss of natural forests, high carbon value forests or forests that perform other important ecosystem services may occur;

- Investments, incentives and potential higher markets prices in agriculture could make crop production more effective or attractive, and contribute to deforestation over the long term or at scale;

- Forest land allocation and collaborative forest management approaches could lead to adverse effects on forest protection and legitimise unsustainable use of forests and forest lands;

- Non-timber forest product business models could result in over-exploitation and/or degradation and/or deforestation (e.g. spread of bamboo across other types of natural forest);

- There are risks of fire and pest/disease outbreaks in plantations;

- Lack of maintenance or abandonment of coastal forests plantations on lands that are classified as protection or special-use forest;

- Inundation in Melaleuca forests may lead to detrimental impacts on biodiversity and greenhouse gas emissions;

- Green credits mechanisms could be used to support non-sustainable investments, with negative impacts on forests and/or greenhouse gas emissions;

- Risks of soil, water and biodiversity degradation associated with the use of agro-chemicals to improve yields.

Measures suggested during this assessment to enhance the co-benefits of REDD+ and reduce risks related to reversals include the following:

- Conservation and protection of natural forests should be prioritised in land use planning processes, applying strategic environmental assessment in land use and sectoral planning, and ensuring that decision-support tools for REDD+ incorporate biodiversity and ecosystem service values;

- Green financial mechanisms should include clear environmental safeguards such as criteria and procedures for screening proposed investments, conducting due diligence checks and monitoring;

- To reduce forest conversion to agriculture, a monitoring and traceability system should be developed, complemented by strengthening the monitoring and enforcement of land use plans in priority hotspots of commodity-driven deforestation;

- Inventories should be conducted on the baseline status of forests to be allocated, as well as studies to understand tenure arrangements, poverty, forest dependency/use and vulnerability. Participatory mapping and consultations on forest land allocation and co-management options should be carried out, including where possible promoting allocation to community groups;

- Access to credit and other livelihood support should be improved, such as on/off farm livelihood improvements allowing households to invest more resources in natural forest protection and restoration;

- Sustainable models identified for agriculture and aquaculture should integrate practices that minimise the use of agro-chemicals and water;

- Non-timber forest product business models and associated practices should promote natural forest protection and enhancement; screening procedures should be developed in order to eliminate inappropriate investments;

- Practical guidelines for afforestation/reforestation and plantation management at site-level should be developed, including site/species selection, plantation design, pest control, fire prevention, etc.;

- Sustainable forest management practices and certification for plantations should be promoted through access improvement to advisory services;

- Detailed studies and consideration of impacts on biodiversity and the wider ecosystem from interventions which affect water levels as well as impacts resulting from construction activities should be conducted and included in Melaleuca sites management plans.

The national guidelines for the development of Provincial REDD+ Action Plans also provide direction on environmental and social benefit and risk assessment of the REDD+ policies and measures set out in these plans[2]. Assessments of environmental and social benefits and risks of REDD+ policies and measures in specific sub-national locations have also been carried out through the Strategic Environmental and Social Assessment (SESA) during the development of the FCPF Emission Reductions Program (ER Program) in the North-Central Coast Region of Viet Nam[3], and through the assessment of Environmental and Social Considerations for the Project for Sustainable Forest Management in the Northwest Watershed Area (SUSFORM-NOW) funded by the Japan International Cooperation Agency (JICA).

In the case of the ER Program in the North-Central Coast Region of Viet Nam, the SESA identified a number of important potential environmental impacts, both positive and negative, including the risk of conversion of natural forest to plantation, and impacts on biodiversity and biodiversity connectivity. For example[2]:

- Natural regeneration and enrichment planting may lead to impacts such as initial minor habitat damage and erosion, and over-exploitation of non-timber forest products, while leading to longer-term benefits due to habitat improvement for biodiversity.

- Afforestation/reforestation with acacia and mixed species and offsetting of infrastructure and other development could lead to possible loss of remnant natural forest to plantations.

- Institutional and capacity building activities should lead to improved forest governance, contributing to protection of biodiversity and improved landscape management.

- Environmental impacts could occur if activities chosen by communities and forest management entities are not supportive of forest or biodiversity conservation supportive.

The following design features have been proposed to mitigate environmental risks in the ER-P:

- Land use planning and design of program field activities: Plantation development activities under the ER Program will be primarily with smallholders rather than through large-scale plantations. Production forests allocated to households with standing natural forest will not be selected for such activities, nor will these take place in protected area sites or sites with high conservation value forests. Plantation establishment will follow sustainable forest management practices and should not replace natural forests, including through mapping of remaining forest areas, awareness, linking plantation development to certification, and tying benefit sharing to the protection of natural forests.

- Codes of practice for plantation development: The Environmental and Social Management Framework (ESMF) identifies the need for clear guidelines to support the development of plantations. These guidelines will prescribe environmental impact management measures in nine main areas: site selection, species selection; management regime, plantation establishment; plantation tending; integrated pest control; fire prevention and control; access and harvesting; and monitoring and evaluation.

- Independent monitoring: The ER Program will support a comprehensive monitoring and evaluation system which will include processes for qualitative and quantitative, bottom-up data collection from the commune for forest cover monitoring and reporting.

[1] NRAP 2017. Vietnamese; English

- Progress on national biodiversity conservation targets

- Content not yet available

- Protected areas and forests in Viet Nam

- Map showing Viet Nam's protected areas

Map showing Viet Nam's protected areas and forest cover[1]

Map showing Viet Nam's protected areas and forest cover[1]

[1] Forest Protection Department (FPD), Ministry of Agriculture and Rural Development

- Map showing Viet Nam's protected areas

- Trends in natural forest cover and other ecosystems

- Table showing natural forest area (ha) nationally in the three categories: total, protection, special use, for two or more periods

Table showing natural forest area (ha) nationally in the three categories: total, protection, special use, for two or more periods[1]

Table showing natural forest area (ha) nationally in the three categories: total, protection, special use, for two or more periods[1]

- Table showing natural forest area (ha) nationally in the three categories: total, protection, special use, for two or more periods

- Trends in natural forest quality

- Table or graph showing the area (ha) of natural forest nationally for at least two periods, and by quality range, i.e. poor natural forest, medium natural forest, rich natural forest

Natural forest by quality range[1]

Natural forest by quality range[1]

- Table or graph showing the area (ha) of natural forest nationally for at least two periods, and by quality range, i.e. poor natural forest, medium natural forest, rich natural forest

- Trends in forest function areas

- Table/figures showing forest area and quality nationally by forest function sub-class (ha). I.e. for each sub-class, show national extent in ha and proportion classified as poor, medium, rich

Forest area and quality nationally by forest function sub-class[1]

Forest area and quality nationally by forest function sub-class[1]

- Table/figures showing forest area and quality nationally by forest function sub-class (ha). I.e. for each sub-class, show national extent in ha and proportion classified as poor, medium, rich

- Forest sector strategy and program outcomes related to conservation

- Content not yet available.

- Contribution of emission reduction programs to conservation

- Content not yet available.

Map showing Viet Nam's protected areas and forest cover[1]

[1] Forest Protection Department (FPD), Ministry of Agriculture and Rural Development

Natural forest by quality range[1]

Forest area and quality nationally by forest function sub-class[1]

Content not yet available

In Viet Nam, the term “forest environmental services” is defined as “the work to supply the use values of the forest environment” and includes:

- Soil protection, reduction of erosion and sedimentation of reservoirs, rivers, and streams;

- Regulation and maintenance of water sources for production and living activities of the society;

- Forest carbon sequestration and retention, reduction of emissions of greenhouse gases through measures for preventing forest degradation and loss of forest area, and for forest sustainable development;

- Protection of natural landscapes and conservation of the biodiversity of forest ecosystems for tourism services;

- Provision of spawning grounds, sources of feeds, and natural seeds, use of water from forests for aquaculture.

To incentivise these forest environmental services means to put in place mechanisms that provide for monetary or non-monetary incentives for their protection.

Viet Nam’s Decree No. 99/2010/ND-CP on Payments for Forest Environmental Services (PFES)[1] defines types of forest environmental services (including carbon sequestration/storage) and creates a mechanism for environmental service users to pay for the services provided by State Forest Management Boards, households and communities. The decree also sets out the methods of payment to a centrally- or provincially-managed fund and how the benefits should be distributed to service providers.

Prime Minister’s Decision No. 30a/2008/NQ-CP supporting rapid and sustainable poverty reduction in 61 poor districts[2] provides a mechanism for poor households to receive funds to invest in planted forests and/or receive support for participating in forest protection and development in contracted areas. Decree No. 75/2015/ND-CP[3] provides a mechanism to support poor and ethnic minority households through the provision of increased financial incentives for their participation in forest protection and development activities.

Decree No. 117/2010/ND-CP on Management and Organisation of Special Use Forests[4] sets out the roles of management boards and their orientations towards supporting forest protection and biodiversity conservation. The decree also makes provisions for buffer-zone investment in support of community/livelihood development in neighbouring communes. Circular No. 78/2011 TT-BNNPTNN[5] provides further details and guidance. The Ministry of Agriculture and Rural Development Circular No. 38/2014/TT-BNN on guidelines for sustainable forest management planning[6] provides for the participation of communities so that they may access socio-economic benefits from sustainable forest management.

The Ministry of Agriculture and Rural Development, and the provincial Departments of Agriculture and Rural Development within their respective localities, are responsible for forest protection and development planning. Forest management boards are responsible for site-level planning, under the oversight of the provincial Departments of Agriculture and Rural Development, and for implementing conservation management and buffer zone development. Provincial, District and Commune People’s Committees are responsible for implementing poverty reduction programmes. Provincial Departments of Agriculture and Rural Development and Provincial Forest Fund agencies are responsible for collecting and distributing payments for environmental services.

[1] Viet Nam’s Decree No. 99/2010/ND-CP on Payments for Forest Environmental Services (PFES). Vietnamese; English

[2] Prime Minister’s Decision 30a/2008/NQ-CP supporting rapid and sustainable poverty reduction in 61 poor districts. Vietnamese; English

[3] Decree No. 75/2015/ND-CP. Vietnamese; English

[4] Decree No. 117/2010/ND-CP on Management and Organisation of Special Use Forests. Vietnamese; English

[5] Circular No. 78/2011 TT-BNNPTNN. Vietnamese; English

[6] MARD Circular No. 38/2014/TT-BNN on guidelines for sustainable forest management planning

The principles of Viet Nam’s National REDD+ Programme (2017)[1] include Principle 1.5 on maximising the benefits of forests and mobilising resources for their protection and management:

‘The REDD+ Programme contributes to progressively shifting priority to improving the quality of natural forest and plantations and reducing forest loss in order to maximise social, economic and environmental benefits; extracting more value from the environmental services from forests, and mobilising financial resources for the protection and sustainable development of forests.

A number of policies and measures in the National REDD+ Programme also aim to improve the provision of incentives for the conservation of forests, including natural forests and their biodiversity and ecosystem services. These include:

- Improving forest governance and livelihoods for people living near and in the forest, such as through supporting collaborative management of natural forests and employment and livelihood programmes for people in hotspots of deforestation and forest degradation;

- Piloting, evaluating and replicating sustainable models for natural forests enhancement, protection and conservation, including cooperation between forest owners, local communities and the private sector on business models contributing to forest conservation (e.g. through non-timber forest products and other environmental services);

- Enhancing the economic and financial environment for forests, such as though ‘green’ investment and credit mechanisms for forest protection and development, developing and piloting economic valuation of forests with integration of forest values into national financial processes, and assessing the feasibility of a domestic carbon market.

Information under Safeguard B2.3 on benefit sharing is also relevant to this safeguard on incentives for conservation. As noted under B2.3, as part of the implementation of the National REDD+ Programme, the Government of Viet Nam will issue detailed guidance on the implementation of a REDD+ benefit sharing mechanism, and on a co-management mechanism for Special Use Forests (SUFs), drawing on the results of pilot activities on REDD+ benefit distribution[2], and on a benefit sharing mechanism in the management, protection and development of SUFs[3]. The NRAP (2017) also specifies activities to develop and implement financial management mechanisms for REDD+, including an appropriate incentive delivery system/benefit distribution system, involving assessment of current and potential incentive mechanisms for forest protection and development, issuing of a regulation on forest carbon rights, and finalisation of a REDD+ benefit distribution system, mainstreamed into Viet Nam's 'forest incentives landscape' (E4.1.1). Please see Safeguard B2.3 for more information.

The following information shows outcomes related to

The incentive and benefit sharing mechanisms identified for REDD+ in Viet Nam. These include the results of the REDD+ benefits sharing mechanism as well as national trends in forest protection contracts and Payments for Forest Environmental Services (PFES). See links:

B2.3.3. Outcomes of REDD+ benefit-sharing

B2.2.6. Trends in land use certificates in conflict

In the Viet Nam context, this safeguard element is understood as creating and implementing policies and measures that seek to enhance the socio-cultural, economic, ecological, biological, climatic and environmental, contributions (or benefits) provided by forest resources. The policies and measures of Viet Nam’s National REDD+ Programme, aim to enhance both environmental and social benefits.

Viet Nam’s policy framework, including the National Forest Development Strategy (2006-2020)[1], the National Forest Sector Master Plan (2011-2020)[2], the National Target Program on Sustainable Forest Development (2016-2020)[3], and the National Target Program on New Rural Development and Poverty Alleviation (2016-2020)[4], emphasises that the forest sector should contribute to economic growth, poverty alleviation and environmental protection.

The Forestry Law (2017) requires that “sustainable forest management, harvesting and use of forests must go hand in hand with conservation of natural resources as well as enhancing forest economic, cultural and historical values, protecting the environment, responding to climate change, and improving people’s livelihoods”[5].

[1] National Forest Development Strategy (2006-2020)

[2] National Forest Sector Master Plan (2011-2020)

[3] National Target Program on Sustainable Forest Development (2017-2020)

[4] National Target Program on New Rural Development and Poverty Alleviation (2016-2020)

[5] The Forestry Law (2017, effective 1 January 2019), Article 10. Vietnamese; English

The National REDD+ Programme (NRAP, 2017)[1] includes a number of policies and measures that aim to enhance both environmental and social benefits, including: supporting integrated planning processes towards achieving the national forest cover target; promoting public participation in environmental and social impact assessments to improve land use decision making (enhancing environmental and social benefits and minimising risks); supporting farmers to develop sustainable agricultural models for key commodities; promoting forest land allocation to households and communities and sustainable livelihoods for forest dependent communities; promoting sustainable forestry; developing methods for calculating the Total Economic Value (TEV) of forests and including it in future land use decision making.

Environmental and social co-benefits and risks of the NRAP policies and measures have been assessed, and co-benefit enhancement and risk mitigation measures suggested. The key environmental and social co-benefits of REDD+ implementation in Viet Nam include the following:

- Conservation of biodiversity through maintaining natural forests or restoring forest ecosystems, and through maintained or improved connectivity of forest habitats;

- Improved, or maintained, supply of forest goods and ecosystem services (natural capital);

- Improved access to, and strengthened use rights over, lands and forest resources (natural capital);

- Rural employment opportunities, improved incomes and sustainable/diversified livelihoods from forestry activities, including from forest protection, as well as from non-forestry activities (financial capital) for rural and forest-dependent households and communities, especially the poor;

- Improved awareness, knowledge and capacity (human capital) among beneficiary populations and civil society participating in REDD+ policies and measures;

- Improved connections and networks (social capital) among communities and civil society to effect positive outcomes for rural forest-dependent poor and other vulnerable groups;

- Improved community infrastructure (physical capital) for poor and remote communities;

- Increased resilience and adaptation to climate change and its associated effects;

- Improved governance framework for land and forest use enhancing the potential for more secure livelihoods through positive transformations to enabling structures and processes.

Key environmental and social risks of REDD+ implementation in Viet Nam include:

- Ongoing loss of natural forests, high carbon value forests or forests that perform other important ecosystem services;

- Conversion of natural non-forest habitats impacting biodiversity, ecosystem services, soil carbon stocks and ecological connectivity;

- Loss of productive assets, access or use rights to forests/forestry lands and, therefore, increasing land tenure and use conflicts, as well as reduced access to resources for subsistence/livelihoods;

- Lack of transparency, non-inclusivity and/or use of manipulation in consultation process in social and environmental impact assessments;

- Investments, incentives and potential higher markets prices in agriculture could make crop production more effective or attractive and contribute to deforestation over the long term or at scale;

- Risks of soils, water, biodiversity degradation with the use of agro-chemicals to improve yields;

- Financial mechanisms may better serve the interests of private sector compared to smallholders, and/or increased profitability for private sector at the expense of smallholders;

- Increased vulnerability of farmers/smallholders to economic shocks or trends;

- Forest land allocation and collaborative management approaches could lead to adverse effects on forest protection and legitimise unsustainable use of forests and forest lands;

- Non-timber forest product business models could result in over-exploitation of non-timber forest products and/or degradation/deforestation for their production (e.g. spread of bamboo over natural forest);

- Inequitable benefit distribution, social exclusion and elite capture;

- Poor plantation planning and management and impacts on biodiversity and soils;, and risks of pests, disease infestations and fires in plantations;

- Displacement of land use into forest areas;

- Lack on maintenance or abandonment of coastal forests plantations on lands classified as protection or special-use forests;

- Inundation in Melaleuca forest leading to detrimental impacts on biodiversity and greenhouse gas emissions;

- Green credit mechanisms could be used for non-sustainable investments.

A range of measures to enhance these social and environmental benefits have been suggested through the assessment of the benefits and risks of the NRAP policies and measures. These are also discussed under other safeguards, and include the following suggestions:

- Decision support tools for integrated land use planning, as well as consultations for strategic environmental assessment/environmental impact assessment should integrate social parameters to avoid or mitigate access and use restrictions and the loss of productive assets and livelihoods. Special attention should be given to the inclusion of the poorest communities, ethnic minorities and gender issues into the process.

- Forest land allocation procedures should be clarified and properly implemented; these processes should also be combined with other supporting investments in community/household abilities to develop, manage and protect forest land effectively.

- Plantation and sustainable forest management activities should maintain a focus on including communities and addressing social safeguards issues, e.g. promoting long rotation forestry and sustainable forest management for smallholders and community forestry cooperatives.

- Conservation and protection of natural forests should be prioritised in land use planning processes, applying strategic environmental assessment in land use and sectoral planning, and ensuring that decision-support tools for REDD+ incorporate biodiversity and ecosystem service values.

- Green financial mechanisms should include clear environmental safeguards such as criteria and procedures for screening proposed investments, conducting due diligence checks and monitoring;

- Inventories should be conducted on the baseline status of forests to be allocated, as well as studies to understand tenure arrangements, poverty, forest dependency/use and vulnerability. Participatory mapping and consultations on forest land allocation and co-management options should be carried out, including where possible promoting allocation to community groups.

- Access to credit and other livelihood support should be improved, such as on/off farm livelihood improvements allowing households to invest more resources in natural forest protection and restoration.

- Sustainable models identified for agriculture and aquaculture should integrate practices that minimise the use of agro-chemicals and water.

- Non-timber forest product business models and associated practices should promote natural forest protection and enhancement; screening procedures should be developed in order to eliminate inappropriate investments.

- Practical guidelines for afforestation/reforestation and plantation management at site-level should be developed, including site/species selection, plantation design, pest control, fire prevention, etc.

- Sustainable forest management practices and certification for plantations should be promoted through access improvement to advisory services.

- Detailed studies and consideration of impacts on biodiversity and the wider ecosystem from interventions which affect water levels as well as impacts resulting from construction activities should be conducted and included in Melaleuca sites management plans.

The national guidelines for the development of Provincial REDD+ Action Plans also provide direction on environmental and social benefit and risk assessment of the REDD+ policies and measures set out in these plans[2]. Assessments of environmental and social benefits and risks of REDD+ policies and measures in specific sub-national locations have also been carried out through the Strategic Environmental and Social Assessment (SESA) during the development of the FCPF Emission Reductions Program (ER Program) in the North-Central Coast Region of Viet Nam[3], and through the assessment of Environmental and Social Considerations for the Project for Sustainable Forest Management in the Northwest Watershed Area (SUSFORM-NOW) funded by the Japan International Cooperation Agency (JICA).

The Ministry of Agriculture and Rural Development is the focal point ministry for the development and implementation of the National REDD+ Programme. Provincial Departments of Agriculture and Rural Development are responsible for the development of Provincial REDD+ Action Plans for appraisal and approval by the Provincial People’s Committees.

The ER Program in the North-Central Coast Region of Viet Nam has identified a number of potential and priority non-carbon benefits in three broad categories: socio-economic, environmental and governance. The priority non-carbon benefits for the ER Program are as follows:

- Socio-economic

- Maintaining Sustainable Livelihoods, Culture and Community

- Valuing Forest Resources

- Income Generation and Employment

- Environmental

- Promotion of Climate-Smart Agriculture

- Conservation and Protection of Biodiversity

- Protection and Maintenance of Ecosystems Services

- Governance

- Strengthening of Village Level Socially Inclusive Governance

- Forest Governance and Management

- Improved Land Tenure Regime

- Participatory Land Use Planning

[2] MARD Decision No. 5414/2015/QD-BNN-TCLN on the approval of guidelines for the development of Provincial REDD+ Action Plans.

Content not yet available

- Trends in forest owners

- Trends in land use certifications

Status and trends in land certificates in forested provinces[1]

Poverty rate by province and municipality, 2006-2016[1]

| Province / city | 2006 | 2010 | 2016 |

| WHOLE COUNTRY | 15.5 | 14.2 | 5.8 |

| Red River Delta | 10 | 8.3 | 2.4 |

| Ha Noi | 3 | 5.3 | 1.3 |

| Ha Tay | 12.4 | .. | .. |

| Vinh Phuc | 12.6 | 10.4 | 2.9 |

| Bac Ninh | 8.6 | 7 | 1.6 |

| Quang Ninh | 7.9 | 8 | 3.7 |

| Hai Duong | 12.7 | 10.8 | 2.3 |

| Hai Phong | 7.8 | 6.5 | 2.1 |

| Hung Yen | 11.5 | 11.1 | 2.6 |

| Thai Binh | 11 | 10.7 | 3.7 |

| Ha Nam | 12.8 | 12 | 4.4 |

| Nam Dinh | 12 | 10 | 3 |

| Ninh Binh | 14.3 | 12.2 | 4.3 |

| Northern midlands and mountain areas | 27.5 | 29.4 | 13.8 |

| Ha Giang | 41.5 | 50 | 20.8 |

| Cao Bang | 38 | 38.1 | 21.9 |

| Bac Kan | 39.2 | 32.1 | 15.8 |

| Tuyen Quang | 22.4 | 28.8 | 12 |

| Lao Cai | 35.6 | 40 | 18.1 |

| Yen Bai | 22.1 | 26.5 | 17.5 |

| Thai Nguyen | 18.6 | 19 | 7.1 |

| Lang Son | 21 | 27.5 | 14.5 |

| Bac Giang | 19.3 | 19.2 | 6.3 |

| Phu Tho | 18.8 | 19.2 | 6.3 |

| Dien Bien | 42.9 | 50.8 | 26.1 |

| Lai Chau | 58.2 | 50.2 | 27.9 |

| Son La | 39 | 37.9 | 20 |

| Hoa Binh | 32.5 | 30.8 | 13.4 |

| Northern Central area and Central coastal area | 22.2 | 20.4 | 8 |

| Thanh Hoa | 27.5 | 25.4 | 9.6 |

| Nghe An | 26 | 24.8 | 10.4 |

| Ha Tinh | 31.5 | 26.1 | 11 |

| Quang Binh | 26.5 | 25.2 | 10.6 |

| Quang Tri | 28.5 | 25.1 | 9.1 |

| Thua Thien-Hue | 16.4 | 12.8 | 3.7 |

| Da Nang | 4 | 5.1 | 0.5 |

| Quang Nam | 22.8 | 24 | 8.4 |

| Quang Ngai | 22.5 | 22.8 | 9.2 |

| Binh Dinh | 16 | 16 | 7.5 |

| Phu Yen | 18.5 | 19 | 6.4 |

| Khanh Hoa | 11 | 9.5 | 3.8 |

| Ninh Thuan | 22.3 | 19 | 6.5 |

| Binh Thuan | 11 | 10.1 | 2.3 |

| Central Highlands | 24 | 22.2 | 9.1 |

| Kon Tum | 31.2 | 31.9 | 14.2 |

| Gia Lai | 26.7 | 25.9 | 13.5 |

| Dak Lak | 24.3 | 21.9 | 7.3 |

| Dak Nong | 26.5 | 28.3 | 12.8 |

| Lam Dong | 18.3 | 13.1 | 4.5 |

| South East | 3.1 | 2.3 | 0.6 |

| Binh Phuoc | 10.5 | 9.4 | 5.1 |

| Tay Ninh | 7 | 6 | 1.5 |

| Binh Duong | 0.5 | 0.5 | 0 |

| Dong Nai | 5 | 3.7 | 0.5 |

| Ba Ria - Vung Tau | 7 | 6.8 | 0.8 |

| Ho Chi Minh city | 0.5 | 0.3 | .. |

| Mekong River Delta | 13 | 12.6 | 5.2 |

| Long An | 8.7 | 7.5 | 4.2 |

| Tien Giang | 13.2 | 10.6 | 5.3 |

| Ben Tre | 16.2 | 15.4 | 7.1 |

| Tra Vinh | 21.8 | 23.2 | 10 |

| Vinh Long | 11 | 9.5 | 4.3 |

| Dong Thap | 12.1 | 14.4 | 5.8 |

| An Giang | 9.7 | 9.2 | 2.7 |

| Kien Giang | 10.8 | 9.3 | 2.7 |

| Can Tho | 7.5 | 7.2 | 1.7 |

| Hau Giang | 15 | 17.3 | 7.7 |

| Soc Trang | 19.5 | 22.1 | 8.7 |

| Bac Lieu | 15.7 | 13.3 | 6.9 |

| Ca Mau | 14 | 12.3 | 4 |

[1] Viet Nam General Statistics Office, https://www.gso.gov.vn/default_en.aspx?tabid=783

Map showing production forests nationally[1]

[1] Forest Protection Department (FPD), Ministry of Agriculture and Rural Development

National production of wood (1000 m3) by kinds of economic activity [1]

|

| 2005 | 2010 | 2015 |

| TOTAL | 2,996.4 | 4,042.6 | 9,199.2 |

| State | 915.4 | 1,376.8 | 2,733.8 |

| Non-State: | 2,041.5 | 2,612.5 | 6,344.4 |

| Collective | 2.2 | 3.0 | 6.7 |

| Private | 1,999.1 | 2,555.2 | 6,208.4 |

| Household | 40.2 | 54.3 | 129.3 |

| Foreign invested sector | 39.5 | 53.3 | 121.0 |

| Index (Previous year = 100) - % | |||

| TOTAL | 114.0 | 107.3 | 119.4 |

| State | 109.1 | 109.5 | 116.0 |

| Non-State: | 114.1 | 106.2 | 120.9 |

| Collective | 122.2 | 120.0 | 117.3 |

| Private | 116.3 | 106.2 | 121.0 |

| Household | 117.2 | 107.3 | 120.0 |

| Foreign invested sector | 116.5 | 107.2 | 121.1 |

Gross output of wood (1000 m3) by province by cities, provinces and year[1]

| Administrative unit | 2005 | 2010 | 2015 |

| Nationally | 2996.4 | 4042.6 | 9199.2 |

| Red River Delta | 157 | 187.3 | 490.6 |

| Ha Noi | 2.3 | 10 | 9.7 |

| Ha Tay | 6.3 | .. | .. |

| Vinh Phuc | 27.1 | 27.8 | 26.6 |

| Bac Ninh | 4.9 | 4 | 4.8 |

| Quang Ninh | 54.2 | 104.6 | 395 |

| Hai Duong | 1.9 | 2.5 | 1.4 |

| Hai Phong | 10.5 | 6.7 | 3 |

| Hung Yen | 9.1 | 5 | 3.1 |

| Thai Binh | 4.6 | 3.9 | 3 |

| Ha Nam | 12.5 | 3.9 | 2 |

| Nam Dinh | 7 | 7.5 | 7.3 |

| Ninh Binh | 16.6 | 11.4 | 34.7 |

| Northern midlands and mountain areas | 996.7 | 1328.1 | 2866 |

| Ha Giang | 52.3 | 73 | 100.7 |

| Cao Bang | 23.5 | 31.5 | 19.8 |

| Bac Kan | 27.5 | 53.8 | 148.4 |

| Tuyen Quang | 152 | 225.7 | 661 |

| Lao Cai | 32.4 | 53.9 | 53 |

| Yen Bai | 148.6 | 200.1 | 450 |

| Thai Nguyen | 27.1 | 50.7 | 171.1 |

| Lang Son | 64.1 | 75.3 | 80 |

| Bac Giang | 39.1 | 62.7 | 400.1 |

| Phu Tho | 150.4 | 273.5 | 437.9 |

| Dien Bien | 65.7 | 35.1 | 18.6 |

| Lai Chau | 5.5 | 9.4 | 8 |

| Son La | 53.4 | 43.9 | 42.1 |

| Hoa Binh | 155.1 | 139.5 | 275.3 |

| Northern Central/Central coastal area | 833.2 | 1237.7 | 4388 |

| Thanh Hoa | 33.7 | 51.3 | 398.5 |

| Nghe An | 93.5 | 125.7 | 351.2 |

| Ha Tinh | 47.5 | 84.4 | 263.4 |

| Quang Binh | 37.3 | 74 | 226.4 |

| Quang Tri | 44.6 | 105.7 | 401 |

| Thua Thien-Hue | 54.2 | 82.5 | 511.9 |

| Da Nang | 23.5 | 24.2 | 21.4 |

| Quang Nam | 128.7 | 189 | 702 |

| Quang Ngai | 151.4 | 185.5 | 715.4 |

| Binh Dinh | 127.3 | 196 | 680.2 |

| Phu Yen | 11.7 | 30.5 | 44.5 |

| Khanh Hoa | 39.8 | 35.1 | 28.5 |

| Ninh Thuan | 3.3 | 7 | 1.4 |

| Binh Thuan | 36.7 | 46.8 | 42.2 |

| Central Highlands | 309.3 | 416.5 | 456.6 |

| Kon Tum | 38.4 | 16.7 | 22.4 |

| Gia Lai | 118 | 220.7 | 120.9 |

| Dak Lak | 79.9 | 49.6 | 182.6 |

| Dak Nong | 25.4 | 33.8 | 8.8 |

| Lam Dong | 47.6 | 95.7 | 121.9 |

| South East | 90.4 | 262.8 | 323.8 |

| Binh Phuoc | 7.1 | 20.6 | 12.5 |

| Tay Ninh | 52 | 68.5 | 66.8 |

| Binh Duong | 1.3 | 1.2 | 10.1 |

| Dong Nai | 13.8 | 74.8 | 139.1 |

| Ba Ria - Vung Tau | 2.2 | 84 | 81.5 |

| Ho Chi Minh city | 14 | 13.7 | 13.8 |

| Mekong River Delta | 609.8 | 610.1 | 674.2 |

| Long An | 84.7 | 86.2 | 78.7 |

| Tien Giang | 74 | 80 | 58 |

| Ben Tre | 7.1 | 2.7 | 2.7 |

| Tra Vinh | 60.4 | 77.2 | 78.4 |

| Vinh Long | 18.6 | 18.1 | 17.6 |

| Dong Thap | 98.7 | 112.1 | 96.9 |

| An Giang | 58.4 | 51 | 74 |

| Kien Giang | 57.6 | 42.9 | 38.1 |

| Can Tho | 7.6 | 4.7 | 4.2 |

| Hau Giang | 9.1 | 10.1 | 10.8 |

| Soc Trang | 38.8 | 38.7 | 33 |

| Bac Lieu | 2.9 | 2.9 | 2.4 |

| Ca Mau | 91.9 | 83.5 | 179.4 |

[1] General Statistics Office of Viet Nam. 2018. Gender Statistics in Viet Nam 2016. https://www.gso.gov.vn/default_en.aspx?tabid=778

Table showing Timber harvest by province [1]

Content not yet available

Content not yet available’